Portative organs and “portative organs”

Our world is made of words.

What happens when the same name is given to two fundamentally different models of the same instrument? Confusion.

Those of you who are used to early music concerts have probably listened to Renaissance and Baroque ensembles that use a little organ which is transportable and works with electricity. Nowadays this little organ is often called a “portative organ” (or “positive organ”).

Since this name is widespread people often ask: “what is the relation of this instrument to the medieval portative organ?”

Here an example of this instrument and its use:

Is this “portative organ” the same as the medieval portative organ?

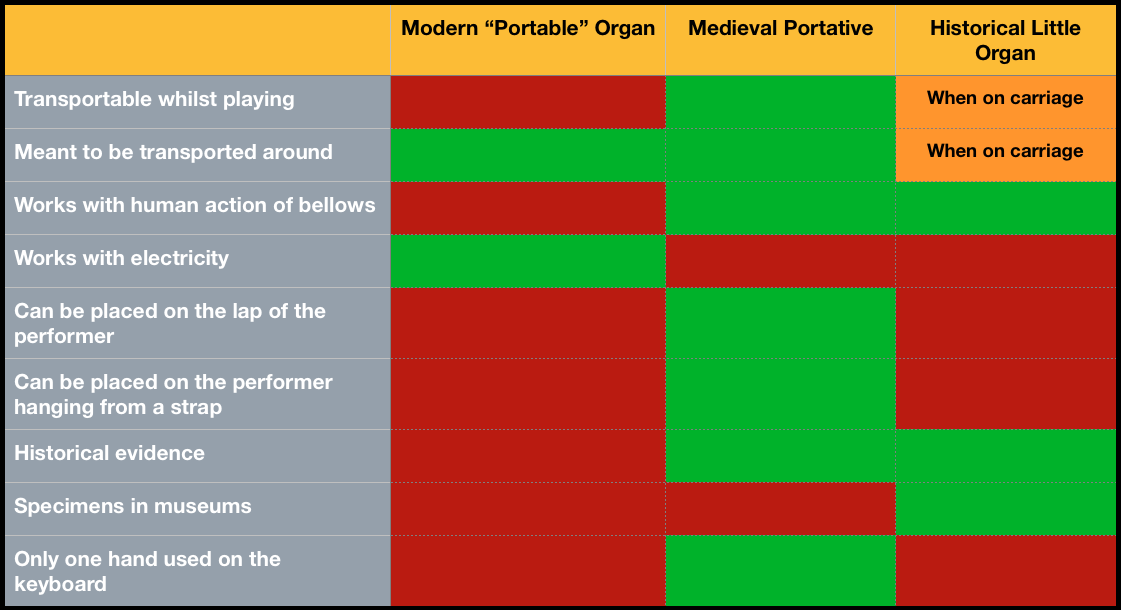

No, it is a completely different instrument and does not represent any chronological continuation of the medieval portative organ tradition. Let’s see the similarities and differences in detail:

Technically speaking both are transportable. However, their function and origin are quite different from each other.

Medieval portative organ

The medieval portative organ is also called organetto (Italian), Portativ (German), orgue de coll (Catalan/Occitan). It is a little organ which is played with one hand on the keyboard and the other on the bellow. There is a lot of historical evidence for medieval portative organs.

Most portative organs of the 13th and 14th centuries are hung from a strap, allowing performers to stand, walk, and dance whilst playing. This more fully justifies the use of the word ”portative” (to carry in Latin).

In the 14th century a bigger version of the portative organ appeared, also played with one hand on the bellow and the other on the keyboard, but now placed on the lap of the seated performer. From the early 16th century its popularity decreased.

The other “portative organ”

At some point in the 20th century a new model developed: a small transportable organ which can adapt to a variety of repertoires from Renaissance to contemporary, and which works with an electric motor. This instrument is mostly used for basso continuo in ensembles.

These rarely imitate concrete historical organ models. And as no new name was assigned to them, the result has been a confusion of many diverse names even amongst players.

Pros

The chameleonic features of the organ give it the advantage of multiple uses. Its size is very convenient for transport and economy of space (it doesn’t require human action on the bellows). It answers the needs of performers who would probably not be able to afford the acquisition of several different models.

In churches where there is already a large organ, the organist may be asked to perform on it alongside other musicians in order to be seen by the public.

Cons

Most of these transportable organs offer a standardised sound for all historical repertoires. In other words, only a few models actually correspond to concrete historical models and their repertoires.

They require electricity to function.

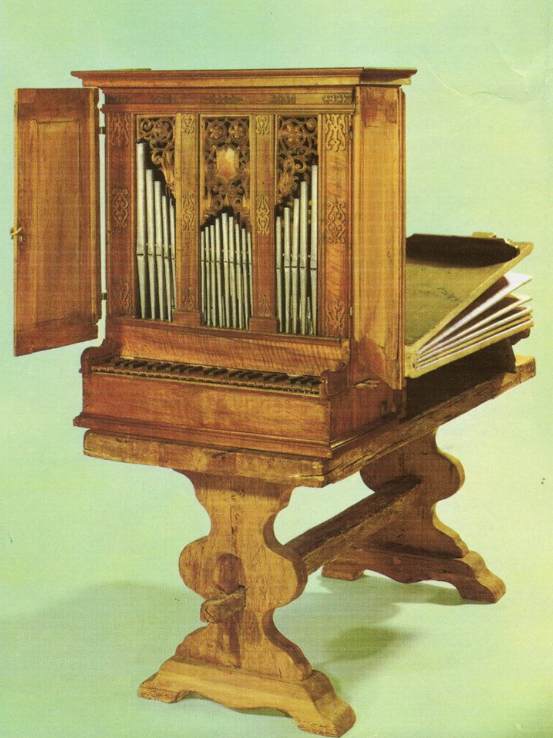

We should differentiate this instrument from reconstructions of historical small organs such as chest organ (English), Truhenorgel (German), organo a cassapanca or organo ad ala (Italian), orgue coffre (French), realejo (Spanish). These names have often been used to name the modern “portable” electric organ. All these different languages make reference to the “box” (often with doors) in which the instrument is closed. In my view this is revealing and a good means of visually identifying the type of organ.

Other names that I have seen used for modern transportable electric organs are: “positive organ” and “basso continuo organ“. Some performers who have an aversion to playing on the most standardised models employ further satirical or amusing names.

Let’s summarise then how many different instruments have we considered until here: first, the medieval portative organ, a historical phenomenon of the late middle ages; secondly, the modern transportable electric organ which solves the modern need of having to supply an organ in a venue where there is none (mostly used for basso continuo); and third, little historical organs that work with human action on the bellows and no electricity.

Similarities and differences between the three groups of organs

This table summarises the elements of the three organ models we are dealing with:

Is there historical evidence for the other modern “portable” organ?

Our modern transportable organs might recall older organs but there are two features that allow us to distinguish them from historical ones:

They require electricity to power their motors, something that was not in use before the 20thcentury. Before electricity, bellows occupied a certain physical space and required people to action them. Modern electric transportable organs therefore save on both space and manpower.

Their creation is a modern need responding to a precise demand. The modern transportable organ is an invention triggered by the need for practicality. Transportable organs contain the same elements as any other organ, but confined within a little box allowing easy transportation from one place to another, such as concert venues and rehearsal rooms.

The use of this organ is a phenomenon bound to the popularisation in modern times of organless concert venues. Music conservatories also benefit from having easily movable instruments for transportation from the classroom to the concert hall.

Sometimes the need for a compact and transportable instrument has an impact on certain characteristics of the instrument such as limiting the number of registers for example. Note that modern transportable organs might appear similar to historical organs and might imitate their decorative style. Again, the principal difference lies in their function.

What are the little organs in the Renaissance and Baroque?

You can see plenty of them in museums! Here are some examples in images.

Observe how these organs are different from the modern “portable” organs we are used to see in concert venues.

Many different forms of historical organs can be found. It would be unreasonable to simplify here the number of models: some were placed on a table, others were designed and built as part of a set of furniture in an architectural project, others were little foldable regals…

However, we should always be aware of their function. Often historical performance venues already owned an organ – be it built-in or moveable (see images of table organ and regal). Commonly these places were churches or the court where a large number of the pieces performed were for religious or ceremonial events, and leisure (such as dance music).

Most of the time therefore there was no need to transport a transportable organ in such buildings which often contained instruments. When the need arose – for example on processions – it would have been placed on a carriage and moved around with the performer and the person(s) who actioned the bellows.

Conclusion

I encourage everyone to use the name “portative organ” consciously. I would suggest using it only for the instrument that was historically first referred to as a “portative organ” – the medieval portative organ. Using the name for two different types of organ at the same time creates confusion rather than being helpful.

In relation to the modern transportable electric organ, we should agree on a name that is clear for everyone.

I think being aware of the difference among organ models is relevant. We all are responsible for making nomenclature clearer and communication better every time we name instruments. The more we use it well, the more it will clarify the situation.

If you work in an orchestra you can grow awareness among your colleagues. If you give a concert you can write the suitable name in the programme notes. And if you create a CD you can include the right name in your booklet.

By choosing the names properly we will be helping to understand better which instrument is which.

Next time you encounter someone with doubts about the two “portative organs” you will be able to identify the models and distinguish the differences.

I would like thank Joan Boronat, Saskia Roures and Diego Ares for the exchange of information and images.

Bonus 1

I leave you here a link to a documentary (several short videos of less than 2 minutes each) about the reconstruction of Monteverdi’s organo di legno, one of the few reconstructions of this sort of organ which produces a magnificent sound.

Bonus 2

In this link you will find a master research by Joan Boronat that includes the topic of instrument names and their function from the 16th to the 18th century in the Iberian Peninsula.