Are there organs in the Bible? Part 1

The organ became a powerful Christian symbol; however its biblical origins might be more blur than we thought…

Several people with whom I had conversations have made reference to religious texts (Old Testament and Psalms) as sources for organs. Some of them asked if these religious sources could be the proof that organs and portative organs would have existed much earlier than we think.

First of all it is essential to understand the origin of religious texts which mention instruments and their translations. Not being able to put them in context could bring us to misleading conclusions. Therefore, I have divided this article into two parts:

- the first part gives a background about the sources in the Bible and the challenges of translating the words that refer to instruments;

- the second part focuses on the nomenclatures of instruments we find in the different Bible translations.

What are the religious texts known as the Bible?

Although we know this text nowadays under one single title, in fact the Bible is a group of texts – or more precisely, books – that ended up being grouped together. The texts were written at different times and by different authors.

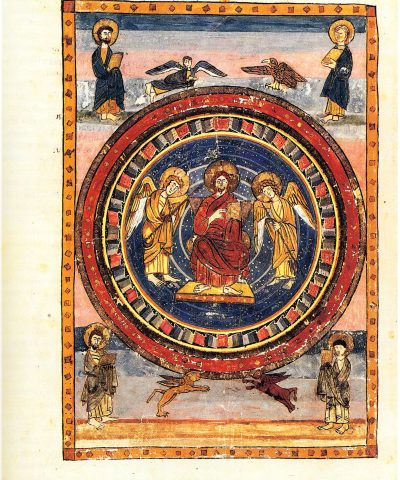

The Bible is used by several religions (Hebrews, Orthodoxes, Catholics…) and played a fundamental role in the development of civilisations and their culture throughout history.

Some of the stories collected in the Bible are in common with other old civilisations of the Near and Middle East. This makes the stories to date even older than the first Hebrew Bible (the Torah).

Earliest version of the Bible: the Hebrew Bible

The contents and order of the various books of the Hebrew Bible were allegedly fixed in the 5th Century B.C. by Ezra HaSofer, one of the Hebrew leaders of his time who led a group of exiles from Babylon to Jerusalem. Ezra seems to have been a scribe and preserved religious texts in a concrete form (I am greatly simplifying the whole story – obviously it is far more complex than that). The role of Ezra in Jerusalem was to guide the Jewish people back towards their roots, traditions and lifestyle according to religious precepts. Since Ezra’s version of the texts, the Hebrew Bible is said to have remained untouched.

At that time the language was written mainly with consonants. Vowels started to be employed from 500-700 CE with a punctuation sign called niqqud. This, however, should not have influenced the interpretation of the text since the texts were all read aloud, allowing the identification of the vowels through the centuries.

EARLIEST SOURCES

The oldest Hebrew sources of Biblical texts which have survived to the present day do not date back to the time when the texts were created or where the narratives occurred.

It is commonly supposed that they were orally transmitted over a period of many centuries before finally being set down in the 5th c. BC by Ezra albeit that Ezra’s written version has never been found.

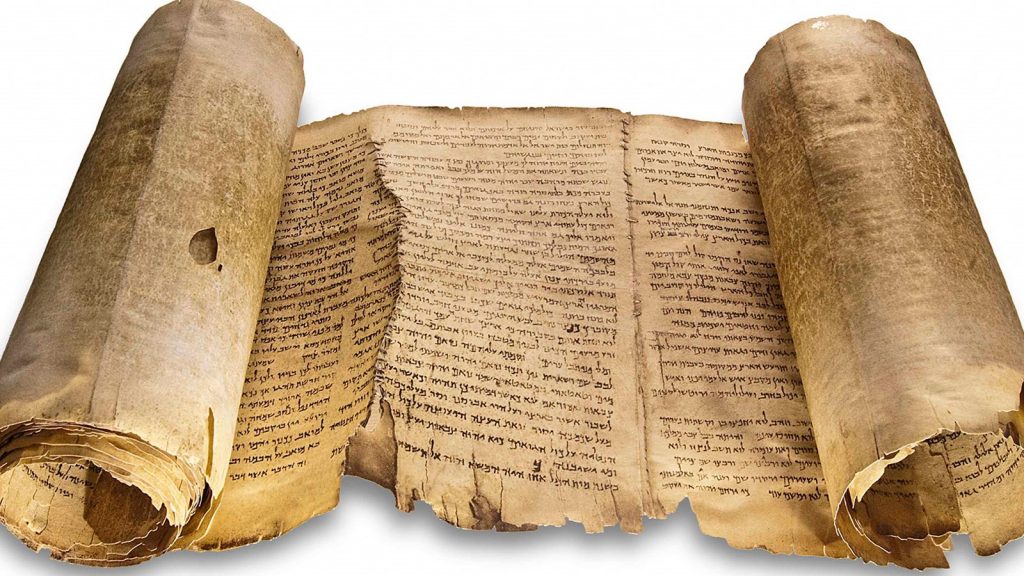

The oldest sources are scrolls from Antiquity and books from the Middle Ages. An example of some of the oldest documents are the Dead Sea Scrolls transmitting fragments of religious biblical texts. Their date is still discussed among scholars, who often date them between the 2nd and 1st century before Christ, or sometimes contemporary with Christ.

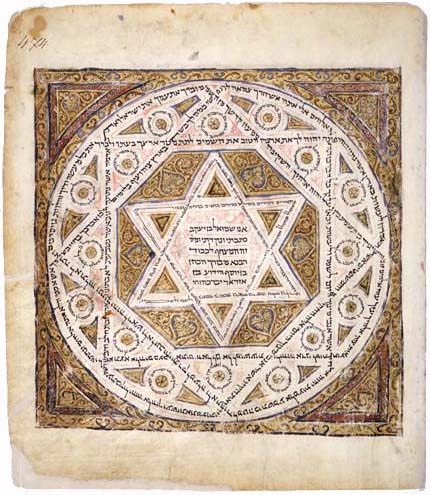

The first complete Hebrew Bible that survived to our days is the Leningrad Codex (now called Saint Petersburg codex) and dates from the 11th century (1008-1009).

Translations into Greek and Latin

The texts of the Bible were originally written in Hebrew and translated into Aramaic and Greek, this last translation is known as Septuagint. The Septuagint was used mostly in Eastern Europe.

The earliest complete Greek translations date from the 4th century CE (although the first copies were supposedly made in the 3rd century BC).

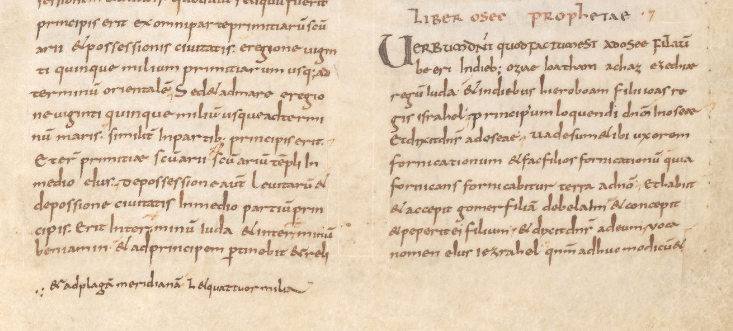

This is when an exceptional initiative from St. Jerome, a Christian priest who lived between ca. 347 and 420 C.E. comes onto the scene. He made two Latin translations: one (partial) from the Greek Septuagint into Latin, and another from the Hebrew into Latin. His versions spread widely over the whole of Western Europe.

What was extraordinary about this undertaking was that whilst most previous translations into Latin had been taken from the Greek Septuagint, Jerome’s Latin version was one of the first to be translated directly from the Hebrew. This translation, commonly known as Vulgata, therefore achieved considerable authority over other existing Latin translations.

EARLIEST SOURCES

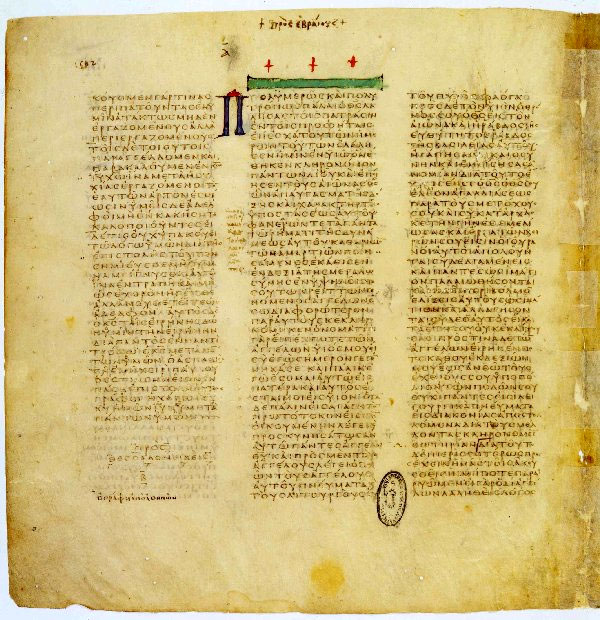

Greek

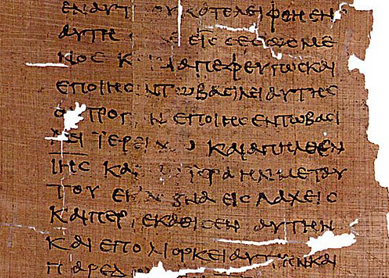

Codex Vaticanus (4th century) is the oldest copy of the Greek Bible.

Codex Sinaiticus (4th century).

Latin

Codex Fuldensis (545) contains a fragment of the New Testament.

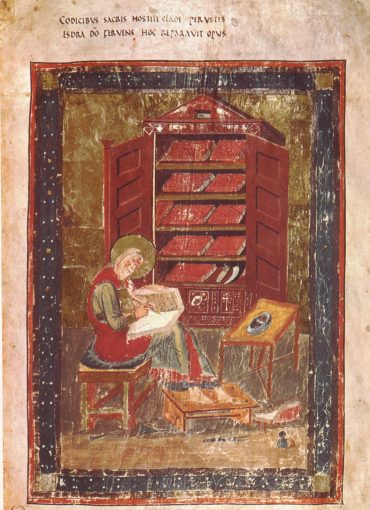

Codex Amiatinus (8th century) is the oldest complete Latin bible.

Mutable text

However, the contents of the Bible have not always been the same!

The Bible does have slightly different content according to each religion because the number and order of books differs: the contents of a Christian Western Europe Bible are not the same as an Eastern one, nor a Hebrew one.

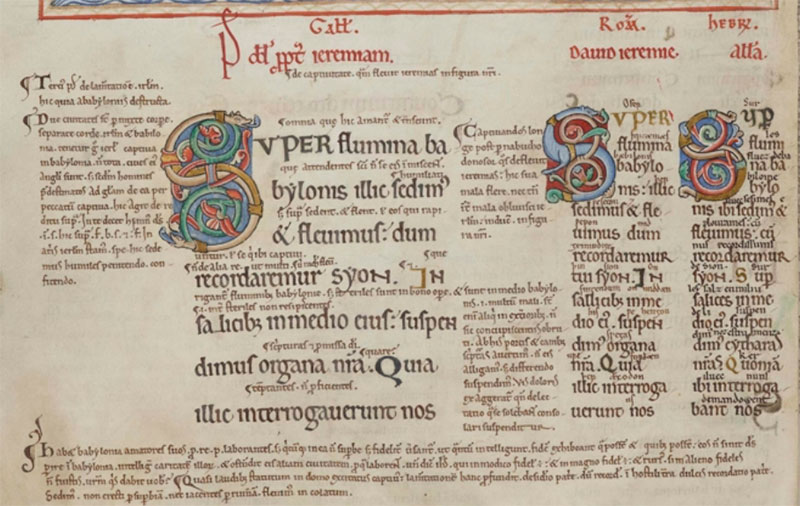

In the Middle Ages the content of what was called the Bible were not standardised for Catholics in Western Europe. Medieval Bible manuscripts would often include a different selection of texts. At the same time in the Middle Ages one could find some of the “books” or groups of books circulating as independent units.

In addition, the same texts could include little variants, different spellings, glosses, etc., making every manuscript unique.

Even if in essence the contents are very similar, the Bible structure as we know today in modern languages was fixed in more modern times as a result from a process that took place from the Renaissance with councils and reformations that shaped and fixed versions for Protestants and Catholics. In addition in more recent times the translation from Latin into modern languages also required a degree of interpretation.

Can time influence the understanding of texts?

The original Hebrew texts were much older than any of the translations. Here there is another factor of essential importance: which musical instruments actually existed at the time these texts were written? And which instruments did the translators in later centuries know?

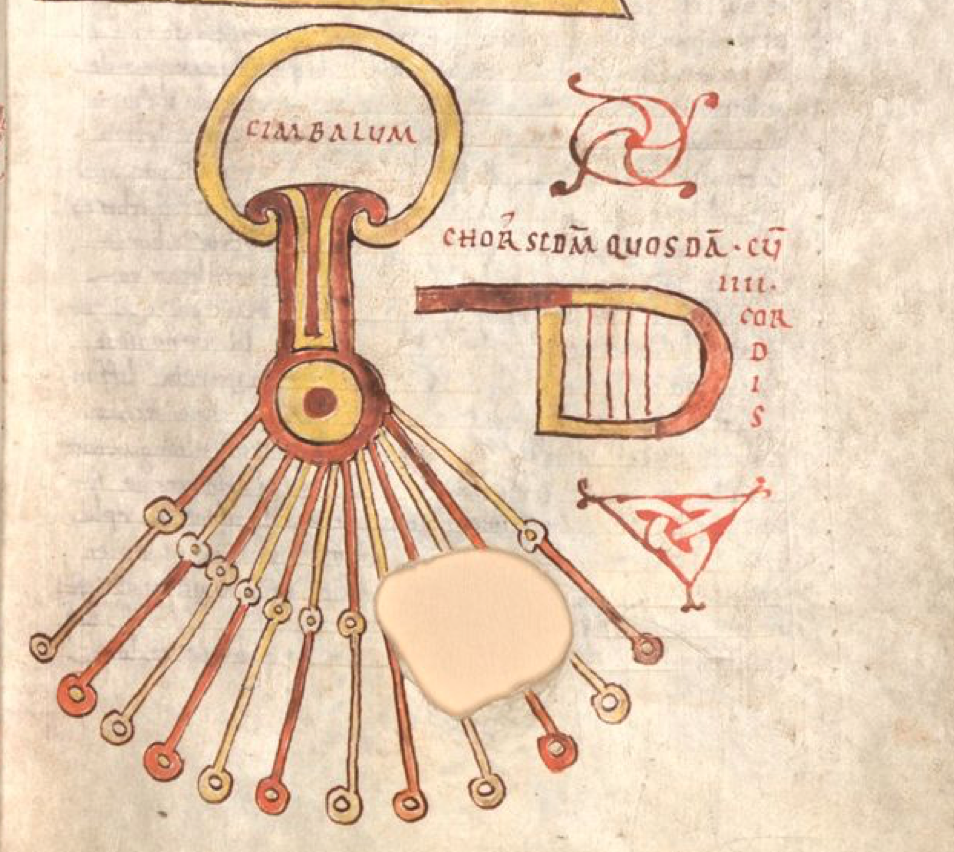

Does an instrument that carries the same name through the centuries exist in the same shape, material and function? Or, if the instrument no longer exists, what is the closest and most similar instrument from which a scribe borrows the nomenclature?

Sometimes we forget that objects are mutable over centuries, their features might change for various reasons.

In the case of the Bible, we know that the Hebrew text is allegedly anchored in the 5th c. BC. Mutations of meaning would come later due to the translations of words that translators cannot recognise.