Super flumina Babylonis: silenced organs?

One of the challenges when researching medieval sources about organs is that the word organ has several meanings, and sometimes it is not clear which is intended in different contexts. The ambiguity of the word is not only a challenging aspect to us today: even in the Middle Ages, the same text spurred different interpretations.

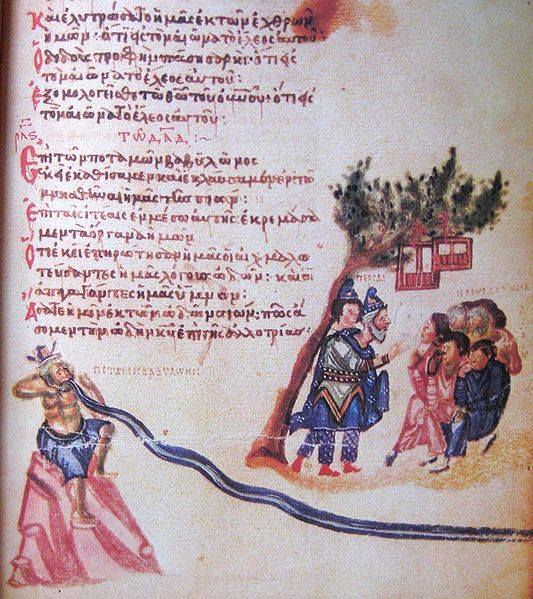

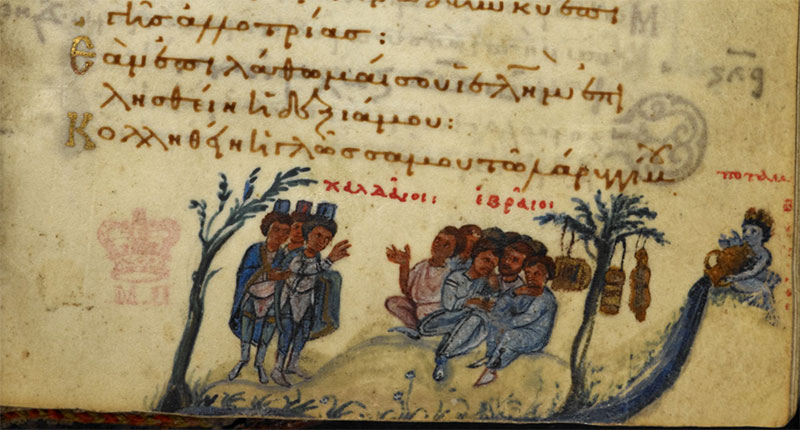

This is the case of psalm 137 (n. 136 in the Septuagint and the Vulgate) and its illustrations in medieval manuscripts. These images seem to interpret the psalm in slightly different ways. It describes a scene during the exile to Babylonia after having fled from Jerusalem as Nebuchadnezzar II took the city in 586 B.C. The Israelites are held in captivity, weeping sadly when remembering Sion. The Babylonians asked them to sing a song accompanied by their instruments. But the Israelites had hung their “organa” on the trees and could not sing. The instruments on the trees represent a rejection – a sorrow that prevents them from singing songs. The Israelites said: “How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?”. This last question – and the verses that follow – state their will to sing only if they are in Jerusalem. Without Jerusalem, there is no joy, hence there could be no singing. The tongue stuck to the roof of the mouth is a powerful image representing the physical impediment that prevents the singing.

I offer the text in three language editions – the English King James Version, the Latin Vulgate, and the Greek Septuaging. They do not represent all possible variants.

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.

We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof.

For there they that carried us away captive required of us a song: and they that wasted us required of us mirth, saying, sing us one of the songs of Zion.

How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?

If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.

If I do not remember thee, let me tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth; if I prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy.

Remember, I Lord, the children of Edom in the day of Jerusalem; who said, rase it, rase it, even to the foundation thereof.

O daughter of Babylon, who art to be destroyed; happy shall he be, that rewardeth thee as thou hast served us.

Happy shall he be, that taketh and dasheth thy little ones against the stones.

Super flumina Babylonis illic sedimus et flevimus, cum recordaremur Sion.

In salicibus in medio ejus suspendimus organa nostra:

quia illic interrogaverunt nos, qui captivos duxerunt nos, verba cantionum: et qui abduxerunt nos: Hymnum cantate nobis de canticis Sion.

Quomodo cantabimus canticum Domini in terra aliena?

Si oblitus fuero, Tui, Jerusalem, oblivioni detur dentera mea.

Adhaereat lingua mea faucibus meis, si non meminero tui; si non proposuero Jerusalem in principio laetitiae meae.

Memor esto, Domine, filiorum Edom, in die Jerusalem; qui dicunt: Exinanite, exinanite usque ad fundamentum in ea.

Filia Babylonis misera! Beatus qui retribuet tibi retribuzione tua quam retribuisti nobis.

Beatus qui tenenti, et allidet parvulos ad petram.

τῷ Δαυιδ ἐπὶ τῶν ποταμῶν Βαβυλῶνος ἐκεῖ ἐκαθίσαμεν καὶ ἐκλαύσαμεν ἐν τῷ μνησθῆναι ἡμᾶς τῆς Σιων

ἐπὶ ταῖς ἰτέαις ἐν μέσῳ αὐτῆς ἐκρεμάσαμεν τὰ ὄργανα ἡμῶν

ὅτι ἐκεῖ ἐπηρώτησαν ἡμᾶς οἱ αἰχμαλωτεύσαντες ἡμᾶς λόγους ᾠδῶν καὶ οἱ ἀπαγαγόντες ἡμᾶς ὕμνον ᾄσατε ἡμῖν ἐκ τῶνᾠδῶν Σιων

πῶς ᾄσωμεν τὴν ᾠδὴν κυρίου ἐπὶ γῆς ἀλλοτρίας

ἐὰν ἐπιλάθωμαί σου Ιερουσαλημ ἐπιλησθείη ἡ δεξιά μου

κολληθείη ἡ γλῶσσά μου τῷ λάρυγγί μου ἐὰν μή σου μνησθῶ ἐὰν μὴ προανατάξωμαι τὴν Ιερουσαλημ ἐν ἀρχῇ τῆςεὐφροσύνης μου

μνήσθητι κύριε τῶν υἱῶν Εδωμ τὴν ἡμέραν Ιερουσαλημ τῶν λεγόντων ἐκκενοῦτεἐκκενοῦτε ἕως ὁ θεμέλιος ἐν αὐτῇ

θυγάτηρ Βαβυλῶνος ἡ ταλαίπωρος μακάριος ὃς ἀνταποδώσει σοι τὸ ἀνταπόδομά σου ὃ ἀνταπέδωκας ἡμῖν

μακάριος ὃς κρατήσει καὶ ἐδαφιεῖ τὰ νήπιά σου πρὸς τὴν πέτραν

Notice that in this English translation, the instrument mentioned is a harp. In other English translations it is often a lyre. In the Greek version of the psalms, the word ὄργανα means “instruments”. When the psalm was translated in the Middle Ages into Latin, it was sometimes translated literally as organa (lit. “instrument” as a generic term) and sometimes as lyra or chytara. Organa can also mean the plural of organ (the specific instrument).

Some of the manuscripts of psalms are miniated and use depictions to represent their content through certain identifying elements. These depictions seem intended to be read: we see the river of Babylonia, the Babylonians ordering the captives to sing (pointing with the finger), the captives making the gesture of weeping (one hand on the cheek), and the hanging instruments in the trees.

At the same time, the depictions work as symbolic references to a well-known scene (for a viewer from the time): the most important point of the psalm is not which instrument is hung, but the fact that the instrument(s) – whatever they are – are not played but placed on the willows. These trees are an important element which highlights the fact that these instrument(s) were unplayed; in other words, silenced.

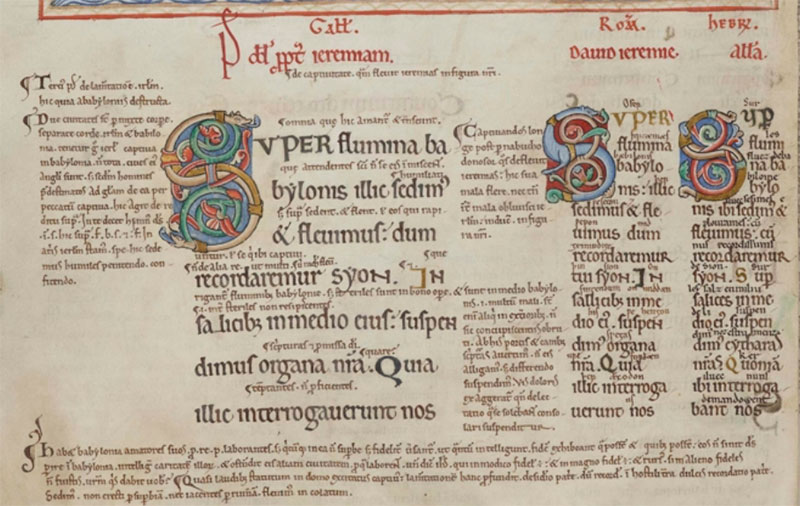

The text of the Eadwine psalter

The Eadwine psalter (Cambridge R-17.1 of the 12th century) is named after a scribe and monk from Canterbury Cathedral. It is an exceptional source that includes three different Latin versions of the psalms, plus two versions in the vernacular: Old English and Norman-French. This allows for immediate comparison and further insight into five different versions of the same psalm.

Two of the Latin versions give the word organa: In salicibus in medio eius suspendimus organa nostra; and the third Latin one uses the word cythara (also in plural): Super salices in medio eius suspendimus cytharas nostras.

The Norman-French translation translates the word as estrumentz – the word for “instruments” in Old French: Sur les salz en miliu de li suspendimus nos estrumentz.

The Old English translates it as swegas which means “sound of an instrument” or “voice”, so again it is not a specific instrument (I thank Adam Brunn for his advice in Old English): On singendum on middaen his we hengon swegas ure.

The instruments hanging on the trees from the Eadwine psalter appear to be plucked string instruments such as the harp and the lyre. The second instrument from the left recalls the one seen in the Stuttgart psalter (see above, first image). In this source the word for the instruments appears up to five times, and coincidentally the number of depicted instruments is five.

Conclusion: what instrument is depicted?

Does each image represent the same instrument? And is it relevant to know exactly which instrument is hung on the trees in all of the manuscripts?

Probably we are putting too much expectation into deciphering which instrument is meant in each iconography. In some cases it is clear, in others ambiguous; and as we see in the sources above, there is no consensus as to which instrument is supposed to illustrate this psalm. Instead, each miniature presents the psalm-scene and its instruments in ways that are determined by certain conventions and contexts, of which nowadays less is known than we would like.

Although some of these illuminated manuscripts are quite old (medieval), the oldest depictions are not even close to the period when the text was created. Thus the illustrated instruments reflect a medieval understanding of what the Greek word organon meant. Thus, rather than authenticity (vis-a-vis the Hebraic past), these miniatures show us the medieval connotations of the word organon.

More to the point, if we expect to be able to read these images as we read twenty-first-century images, we are likely to be disappointed: there is no psalm-instrument depiction of this period that offers the details in a hyper-realistic way. Instead, these depictions convey a set of attributes that allow the viewer to identify the text – which is probably already familiar to him. It then serves as a reminder of the whole story. The fact that the instrument in each text is mutable – organa (as “instrument”), estrumentz (instrument), swegas (sound of instrument), organa (as organ), cythara, and others – next to other elements that remain unchanged – for example the type of tree (willow), or the fact that the instrument is hanging – indicates that some details are more characteristic in capturing the meaning of the psalm than others. Here the type of instrument is secondary, whilst the fact that there is an instrument is the essential point.

The images allow one to read the psalm without text, as if creating a sixth version of the Eadwine psalter. As long as the main attributes of the psalm 137 (136) are recognized by the viewer, the message of the psalm is transmitted. In this case, the main point is the Israelite’s refusal to sing and play instruments after being captured outside Jerusalem: the message is the silenced and non-performed chant, shown by the appearance of untouched hanging instruments. Whether the instrument is an organ or not is secondary.

Did you enjoy this article?

Maintaining the high standard of my work requires much energy and coffee is exactly what I need in order not to run out of energy! Contributions are always welcome.