Are there organs in the Bible? Part 2

In the first part we talked about the background of biblical sources and the challenges of their translations. Here we focus on the challenges of translating what has become the “organ”.

Mysterious ugav

Translating means interpreting to a certain degree. We have even a major challenge when presented by the name of an instrument which nobody seems to know anything about. This is the case with the word עוּגָב (ugav).

Ugav only appears 4 times in the Bible. It is often mentioned together with other instruments in joyful situations. It designates an instrument. But which?

It is surprising that of all the instruments mentioned in the Hebrew Bible ugav appears only four times, less than most of the other instruments. Here are the four places where ugav is mentioned in the Bible in an English translation:

They take the timbrel and harp, and rejoice at the sound of the organ (ugav).

And his brother’s name was Jubal: he was the father of all such as handle the harp and organ (ugav).

My harp also is turned to mourning and my organ (ugav) into the voice of them that weep.

Praise him with the timbre and dancing, praise him with the strings and pipe / organ (ugav).

What do the experts say?

I have been in touch with experts on etymology of Classic Hebrew in order better to understand the word ugav. It transpired that we know less than we would like about the original meaning of ugav. It is an instrument, but we do not know which. The most I could achieve from the research is a hypothesis, but not a statement of fact since precise information from primary sources is missing.

Some scholars (Curt Sachs for example) have pointed at the possibility that the ugav is linked to other similar classic Hebrew roots which suggest this instrument be involved in love chants or love melodies. Also in some books ugav is translated as flute or pipe, following the same arguments.

Dr. Thomas Staubli – a Swiss theologian teaching in Freiburg University – says:

“Archaeology shows that there was not such a thing as an “organ” in the Ancient Near East.”

He explains that no description or depiction from the time of the Bible’s origin seems to describe an instrument similar to the organ.

On the problematics of translations, in 1901 Kathleen Schlesinger – a British music archaeologist – wrote that:

“Although the ugav is translated “organ” in our English version, this is no proof that the organ was known in the days of Moses, for the translators were apparently not versed in musical matters, and have merely given what seemed to them the best equivalent, thus we get for Kithara harp, and for Sambuka sackbut!”

As is well known nowadays, in modern Hebrew an organ is called ugav. However this does not mean that at the time of the origins of the Bible, ugav would mean organ. We have already seen how challenging it is to understand its original meaning in classic Hebrew.

How come we ended up having “organs” in the Bible?

First critical translation: Greek Septuagint

The creation of the Greek translation is the first critical one, because it’s there where the confusion starts. Read Part 1 if you are missing info about the Greek Septuagint.

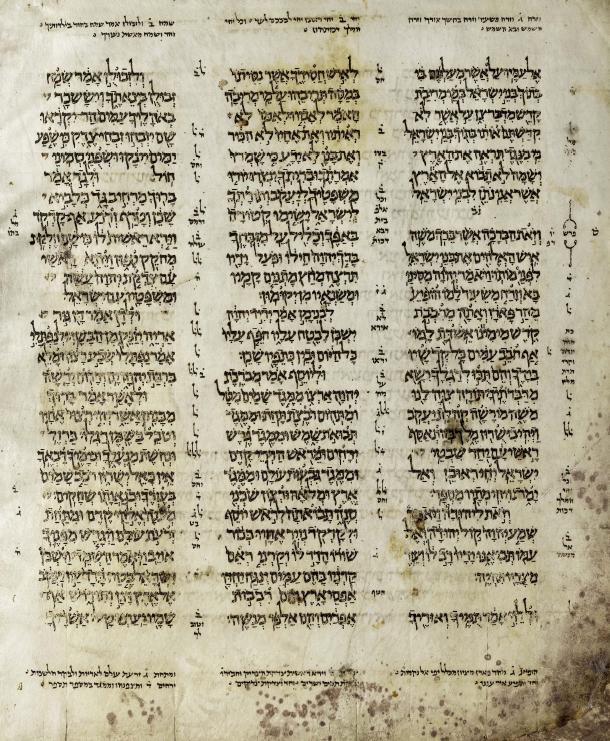

Not all of the four times ugav shows up in the Hebrew version was it translated as organon. It was translated as kithara (Gen 4:21), psalmos (Job 21:12, 30:31), and organon (Psalm 150:4).

In the Septuagint the word ὄργανον (organon) means “instrument”. Any instrument, not one in particular. It is also worth noting that the only sort of organ that was known at the time when the Septuagint was being translated was the hydraulis, the water organ.

Precise information of what the word ὄργανον means in context is missing. So although we can figure out that it is a musical instrument, we have no way of telling precisely which instrument it could be. The question here is: did the translator actually know what an ugav was?

In the Greek version organon is not only used for the Hebrew ugav, but also for other instruments: kle, kinnor and nevel (I thank Dr. Staubli for this information).

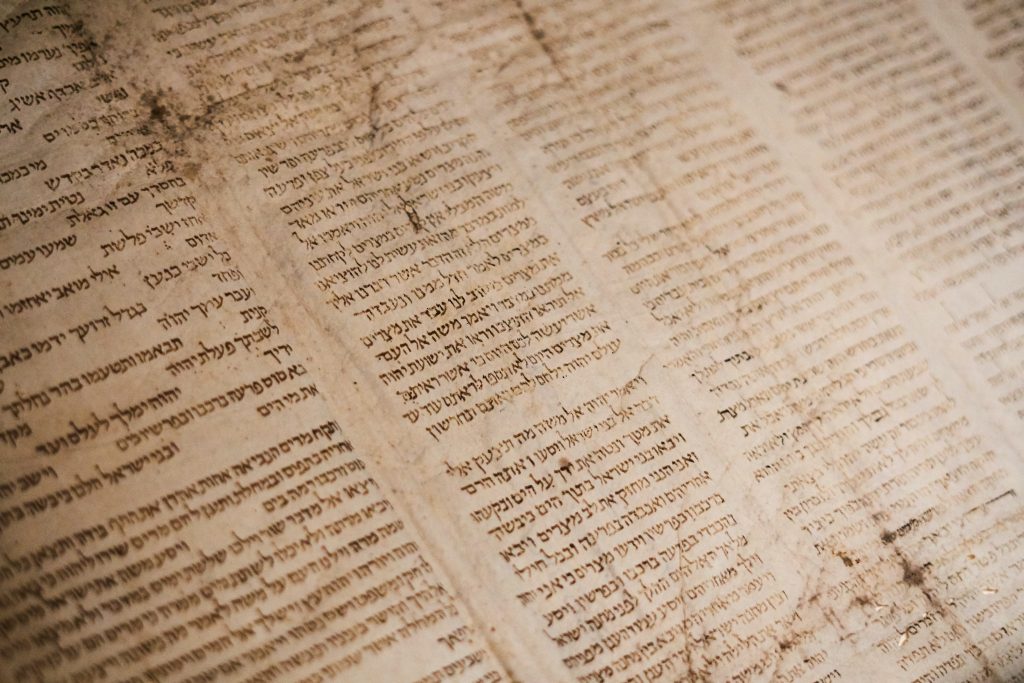

Interestingly enough the first copy of the Septuagint was allegedly made in the 3rd century before Christ, which is “only” two centuries after the official dating of Ezra’s earliest Hebrew Bible. Among the earliest surviving sources of the bible there are a few more sources in Greek than in Hebrew, and that’s why the study of the Septuagint could enable us to find traces of the earliest Hebrew version.

More about the inconsistency on translating organa?

Visit the article “Super flumina Babylonia” to see how a single word like organon can be transformed into many different instruments!

Second critical translation: Latin Vulgate

The second critical transfer of the word is in the Latin translation. Here we should remember that some of the translations had been done from the Greek version, but that Jerome’s more widespread translation was from the Hebrew. Find more about Jerome’s translation in the Part 1 of this article. That means that the Latin version can have influences from both languages. That’s exactly what happens with our ugav!

The Latin version picks up the Greek word organon literally and phonetically translated into the Latin as organum. But now this word is used without consistently taking into consideration the placement of the word organon in the Greek version. Remember we saw how in the Greek version the word ugav, rather than always being translated as organon, was translated differently in different places. Now organon is consistently and indiscriminately replacing the word ugav as it occurs in the Hebrew version.

The Latin organum differs from the Greek organon: it can mean both “instrument” or “organ”. At last we find a word which is clearly related to the organ! In its turn, the Latin organum is not only ambivalent (instrument/organ): it might also refer to different types of organ, both hydraulis or pipe organ.

The Latin translation is the one that linked the idea of “organ” with the Bible and Christianity.

Another problematic translation: Kinnor

A parallel case is the one for the word kinnor, which means string instrument, usually translated as lyre or harp. But in modern times, kinnor in Hebrew is a violin. The most similar and earliest fiddle-like stringed instrument we can trace back in Bible depictions appears in the Middle Ages. Again, a problematic word to translate and to depict.

Conclusion: Do organs and portative organs exist in the Bible?

In conclusion we find that both at the time that the Hebrew and Greek versions of the Bible were first copied there was no such concept as “organ”, and that the words ugav and organon do not in fact designate an organ. Archaeology also shows that in the time when the Bible was constituted organs did not exist in the Ancient Near East (here I would like to thank Dr. Staubli for sharing his research).

The only type of organ known during the time of the translation of the Greek Bible was the hydraulis (water organ), which is not mentioned either.

During Antiquity there is no proof that the organ was used in religious celebrations of Jewish or Eastern European Christians.

From the moment the Latin translation appears, the word organum includes the definition “organ”. At this point the symbolic meaning of the organ grew to such an extent that it became one of the most representative of Christian instruments.

In the Middle Ages we can see plenty of images of organs and portatives related to biblical Latin texts. The organ became an established imaginery of religious centers.

Some very old names of instruments might remain mysterious and uncodified through the centuries, like the enigmatic ugav. However, at some point in history organs began to appear in Jewish sources. Do you want to know how that happened? Stay tuned for the coming article!